Development economics involves the creation of theories and methods that aid in the determination of policies and practices and can be implemented at either the domestic or international level.This may involve restructuring market incentives or using mathematical methods like inter-temporal optimization for project analysis, or it may involve a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods.

Unlike in many other fields of economics, approaches in development economics may incorporate social and political factors to devise particular plans. Also unlike many other fields of economics, there is "no consensus" on what students should know. Different approaches may consider the factors that contribute to economic convergence or non-convergence across households, regions, and countries.

Contents

- 1 Theories of development economics

- 1.1 Mercantilism

- 1.2 Economic nationalism

- 1.3 Post-WWII theories

- 1.4 Linear-stages-of-growth model

- 1.5 Structural-change theory

- 1.6 International dependence theory

- 1.7 Neoclassical theory

- 2 Topics of Research

- 2.1 Economic Development and Ethnicity

- 2.1.1 The Role of “Ethnicity” in Economic Development

- 2.1.2 Economic Development and its Impact on Ethnic Conflict

Theories of development economics

Mercantilism

Main article: MercantilismThe earliest Western theory of development economics was mercantilism, which developed in the 17th century, paralleling the rise of the nation state. Earlier theories had given little attention to development. For example, Scholasticism the dominant school of thought during medieval feudalism, emphasized reconciliation with Christian theology and ethics, rather than development. The 16th- and 17th-century School of Salamanca, credited as the earliest modern school of economics, likewise did not address development specifically.

Major European nations in the 17th and 18th century all adopted mercantilist ideals to varying degrees, the influence only ebbing with the 18th-century development of physiocrats in France and classical economics in Britain. Mercantilism held that a nation's prosperity depended on its supply of capital, represented by bullion (gold, silver, and trade value) held by the state. It emphasised the maintenance of a high positive trade balance (maximising exports and minimising imports) as a means of accumulating this bullion. To achieve a positive trade balance, protectionist measures such as tariffs and subsidies to home industries were advocated. Mercantilist development theory also advocated colonialism.

Economic nationalism

Main article: Economic nationalismFollowing mercantilism was the related theory of economic nationalism, promulgated in the 19th century related to the development and industrialization of the United States and Germany, notably in the policies of the American System in America and the Zollverein (customs union) in Germany. A significant difference from mercantilism was the de-emphasis on colonies, in favor of a focus on domestic production.

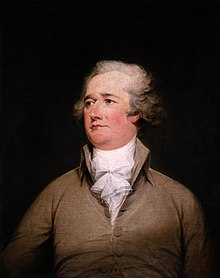

The names most associated with 19th-century economic nationalism are the American Alexander Hamilton, the German-American Friedrich List, and the American Henry Clay. Hamilton's 1791 Report on Manufactures, his magnum opus, is the founding text of the American System, and drew from the mercantilist economies of Britain under Elizabeth I and France under Colbert. List's 1841 Das Nationale System der Politischen Ökonomie (translated into English as The National System of Political Economy), which emphasized stages of growth, proved influential in the US and Germany, and nationalist policies were pursued by politician Henry Clay, and later by Abraham Lincoln, under the influence of economist Henry Charles Carey.

Post-WWII theories

See also: Industrial development and Ragnar Nurkse's Balanced Growth TheoryThe origins of modern development economics are often traced to the need for, and likely problems with the industrialization of eastern Europe in the aftermath of World War II.The key authors are Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, Kurt Mandelbaum, Ragnar Nurkse,and Sir Hans Wolfgang Singer. Only after the war did economists turn their concerns towards Asia, Africa and Latin America. At the heart of these studies, by authors such as Simon Kuznets and W. Arthur Lewis was an analysis of not only economic growth but also structural transformation.

Linear-stages-of-growth model

An early theory of development economics, the linear-stages-of-growth model was first formulated in the 1950s by W. W. Rostow in The Stages of Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, following work of Marx and List. This theory modifies Marx's stages theory of development and focuses on the accelerated accumulation of capital, through the utilization of both domestic and international savings as a means of spurring investment, as the primary means of promoting economic growth and, thus, development. The linear-stages-of-growth model posits that there are a series of five consecutive stages of development which all countries must go through during the process of development. These stages are "the traditional society, the pre-conditions for take-off, the take-off, the drive to maturity, and the age of high mass-consumption"Simple versions of the Harrod–Domar model provide a mathematical illustration of the argument that improved capital investment leads to greater economic growth.

Structural-change theory

Structural-change theory deals with policies focused on changing the economic structures of developing countries from being composed primarily of subsistence agricultural practices to being a "more modern, more urbanized, and more industrially diverse manufacturing and service economy." There are two major forms of structural-change theory; W. Lewis' two-sector surplus model, which views agrarian societies as consisting of large amounts of surplus labor which can be utilized to spur the development of an urbanized industrial sector, and Hollis Chenery's patterns of development approach, which holds that different countries become wealthy via different trajectories. The pattern that a particular country will follow, in this framework, depends on its size and resources, and potentially other factors including its current income level and comparative advantages relative to other nations. Empirical analysis in this framework studies the "sequential process through which the economic, industrial and institutional structure of an underdeveloped economy is transformed over time to permit new industries to replace traditional agriculture as the engine of economic growth."

International dependence theory

International dependence theories gained prominence in the 1970s as a reaction to the failure of earlier theories to lead to widespread successes in international development. Unlike earlier theories, international dependence theories have their origins in developing countries and view obstacles to development as being primarily external in nature, rather than internal. These theories view developing countries as being economically and politically dependent on more powerful, developed countries which have an interest in maintaining their dominant position. There are three different, major formulations of international dependence theory: neocolonial dependence theory, the false-paradigm model, and the dualistic-dependence model. The first formulation of international dependence theory, neocolonial dependence theory, has its origins in Marxism and views the failure of many developing nations to undergo successful development as being the result of the historical development of the international capitalist system.

Neoclassical theory

First gaining prominence with the rise of several conservative governments in the developed world during the 1980s, neoclassical theories represent a radical shift away from International Dependence Theories. Neoclassical theories argue that governments should not intervene in the economy; in other words, these theories are claiming that an unobstructed free market is the best means of inducing rapid and successful development. Competitive free markets unrestrained by excessive government regulation are seen as being able to naturally ensure that the allocation of resources occurs with the greatest efficiency possible and the economic growth is raised and stabilized.

Topics of Research

Development economics also includes topics such as Third world debt, and the functions of such organisations as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. In fact, the majority of development economists are employed by, do consulting with, or receive funding from institutions like the IMF and the World Bank. Many such economists are interested in ways of promoting stable and sustainable growth in poor countries and areas, by promoting domestic self-reliance and education in some of the lowest income countries in the world. Where economic issues merge with social and political ones, it is referred to as development studies.

Economic Development and Ethnicity

A growing body of research has been emerging among development economists since the very late 20th Century focusing on interactions between ethnic diversity and economic development, particularly at the level of the nation-state. While most research looks at empirical economics at both the macro and the micro level, this field of study has a particularly heavy sociological approach. The more conservative branch of research focuses on tests for causality in the relationship between different levels of ethnic diversity and economic performance, while a smaller and more radical branch argues for the role of neoliberal economics in enhancing or causing ethnic conflict. Moreover, comparing these two theoretical approaches brings the issue of endogeneity (endogenicity) into questions. This remains a highly contested and uncertain field of research, as well as politically sensitive, largely due to its possible policy implications.

The Role of “Ethnicity” in Economic Development

Much discussion among researchers centers around defining and measuring two key but related variables: ethnicity and diversity. It is debated whether ethnicity should be defined by culture, language, or religion. While conflicts in Rwanda were largely along tribal lines, Nigeria’s string of conflicts is thought to be – at least to some degree – religiously based. Some have proposed that, as the saliency of these different ethnic variables tends to vary over time and across geography, research methodologies should vary according to the context. Somalia provides an interesting example. Due to the fact that about 85% of its population defined themselves as Somali, Somalia was considered to be a rather ethnically-homogeneous nation. However, civil war caused ethnicity (or ethnic affiliation) to be redefined according to “clan” groups.

There is also much discussion among academia concerning the creation of an index for “ethnic heterogeneity”. Several indices have been proposed in order to model ethnic diversity (with regards to conflict). Easterly and Levine have proposed an ethno-linguistic fractionalization index defined as FRAC or ELF defined by:

Early researchers, such as Jonathan Pool, considered a concept dating back to the account of the Tower of Babel: that linguistic unity may allow for higher levels of development.While pointing out obvious oversimplifications and the subjectivity of definitions and data collection, Pool suggested that we had yet to see a robust economy emerge from a nation with a high degree of linguistic diversity. In his research Pool used the “size of the largest native-language community as a percentage of the population” as his measure of linguistic diversity. Not much later, however, Horowitz pointed out that both highly diverse and highly homogeneous societies exhibit less conflict than those in between. Similarly, Collier and Hoeffler provided evidence that both highly homogenous and highly heterogeneous societies exhibit lower risk of civil war, while societies that are more polarized are at greater risk.As a matter of fact, their research suggests that a society with only two ethnic groups is about 50% more likely to experience civil war than either of the two extremes. Nonetheless, Mauro points out that ethno-linguistic fractionalization is positively correlated with corruption, which in turn is negatively correlated with economic growth. Moreover, in a study on economic growth in African countries, Easterly and Levine find that linguistic fractionalization plays a significant role in reducing national income growth and in explaining poor policies. In addition, empirical research in the U.S., at the municipal level, has revealed that ethnic fractionalization (based on race) may be correlated with poor fiscal management and lower investments in public goods Finally, more recent research would propose that ethno-linguistic fractionalization is indeed negatively correlated with economic growth while more polarized societies exhibit greater public consumption, lower levels of investment and more frequent civil wars.

- 2.1 Economic Development and Ethnicity